IP and intangible asset values shine in High Street closures

9 Feb 2021

Online retailer boohoo, which had already acquired the Debenhams brand intellectual property (IP) in January for £55m, has now picked up Burtons, Dorothy Perkins and Wallis brands from Arcadia for another £25m.

This follows last week’s news that rival online retailer ASOS has bought the Topshop, Topman, Miss Selfridge and sports brand HIIT, also from the bankrupt Arcadia Group.

ASOS paid £265m for the intellectual property and intangible assets, plus £30m for stock, so the brands can continue trading in the short term until they are integrated into the ASOS manufacturing and supply chain.

Neither boohoo nor ASOS are buying any of the relevant brands’ bricks and mortar retail outlets.

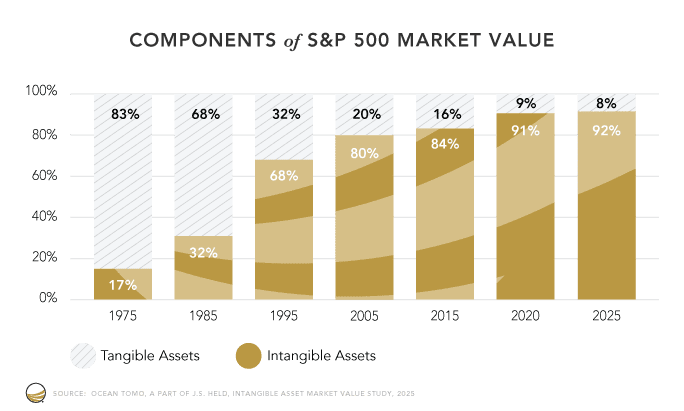

These deals ram home the fact that IP and intangible asset values – trade marks, copyrights, customer databases, designs, know-how, supplier relationships and the like – are now more important to companies than traditional tangible assets such as shops, warehouses, office buildings, stock, raw materials and vehicles.

As Inngot CEO Martin Brassell says: “IP and intangibles are valuable because of their uniqueness, and the ASOS and boohoo deals prove once again that worthwhile value can survive administration. In fact, IP and intangibles may be the only value that endures - the tangible assets these retail brands own, in particular the shops themselves, are much less in demand."

The value of IP when companies get into financial difficulties has become a key issue for lenders, particularly in the retail world. Its assessment is made more problematic by accounting rules that do not reflect the rise of brand valueand technology-related assets. Unless they have bought in the IP in question, companies are restricted in how they can recognise intangible assets on their balance sheet compared with physical, tangible assets.

Even where identifiable, internally-generated IP and intangibles do appear on company balance sheets, these entries are only at cost, and are required to be amortised (written off over time), so their value always appears to be in decline. In the real world, the opposite is often happening.

The fact that ASOS, boohoo and other purchasers are prepared to pay substantial amounts for collapsed retailers’ IP and intangibles shows they think these assets have real value, even as a “gone concern”, whatever the balance sheet may say – or rather, not say.

BooHoo’s purchase of the Debenhams brand and related intangibles is a good example of where the value now lies. Debenhams’ trade marks, designs and copyrights are certainly going to be of value to boohoo; but so too are the details of 6 million customers who bought beauty products from Debenhams and the 1.4 million members of its Beauty Club loyalty scheme. boohoo has definite ambitions to expand its share of the beauty market, and it plans to leverage these new assets to help it do that.

The Laura Ashley story has a slightly different twist. It was bought by US ‘brand rescue’ company Gordon Brothers almost a year ago; in October 2020, Gordon Brothers announced it had signed a deal with Next which will see the latter launch a range of Laura Ashley products in its UK High Street stores and online in Spring 2021.

Significantly, Gordon Brothers’ deal for Laura Ashley included the company’s extensive design archives. Gordon Brothers made it clear that IP licensing was a major factor in the transaction. At the time of its demise, Laura Ashley had around 70 licensees worldwide selling a range of products, and Gordon Brothers plans to expand the number of licensees, so generating even more income from the IP.

The global retail industry was already in the middle of a drawn-out and painful transformation, as the rise of online shopping undercut the traditional retail business model. Reliance on bricks-and-mortar stores, either owned or occupied on relatively inflexible leases, was already an Achilles’ heel, as e-commerce slashed entry costs for new, more nimble rivals.

COVID-19 and lockdown have served to accelerate an already unstoppable process; shoppers were already abandoning bricks-and-mortar stores in favour of buying online. It has, tragically, meant many thousands of retail workers have lost their jobs; but, although little comfort to the people now out of work, the brands, and associated IP and intangible asset values, live on.

Martin Croft

Online retailer boohoo, which had already acquired the Debenhams brand intellectual property (IP) in January for £55m, has now picked up Burtons, Dorothy Perkins and Wallis brands from Arcadia for another £25m.

This follows last week’s news that rival online retailer ASOS has bought the Topshop, Topman, Miss Selfridge and sports brand HIIT, also from the bankrupt Arcadia Group.

ASOS paid £265m for the intellectual property and intangible assets, plus £30m for stock, so the brands can continue trading in the short term until they are integrated into the ASOS manufacturing and supply chain.

Neither boohoo nor ASOS are buying any of the relevant brands’ bricks and mortar retail outlets.

These deals ram home the fact that IP and intangible asset values – trade marks, copyrights, customer databases, designs, know-how, supplier relationships and the like – are now more important to companies than traditional tangible assets such as shops, warehouses, office buildings, stock, raw materials and vehicles.

As Inngot CEO Martin Brassell says: “IP and intangibles are valuable because of their uniqueness, and the ASOS and boohoo deals prove once again that worthwhile value can survive administration. In fact, IP and intangibles may be the only value that endures - the tangible assets these retail brands own, in particular the shops themselves, are much less in demand."

The value of IP when companies get into financial difficulties has become a key issue for lenders, particularly in the retail world. Its assessment is made more problematic by accounting rules that do not reflect the rise of brand valueand technology-related assets. Unless they have bought in the IP in question, companies are restricted in how they can recognise intangible assets on their balance sheet compared with physical, tangible assets.

Even where identifiable, internally-generated IP and intangibles do appear on company balance sheets, these entries are only at cost, and are required to be amortised (written off over time), so their value always appears to be in decline. In the real world, the opposite is often happening.

The fact that ASOS, boohoo and other purchasers are prepared to pay substantial amounts for collapsed retailers’ IP and intangibles shows they think these assets have real value, even as a “gone concern”, whatever the balance sheet may say – or rather, not say.

BooHoo’s purchase of the Debenhams brand and related intangibles is a good example of where the value now lies. Debenhams’ trade marks, designs and copyrights are certainly going to be of value to boohoo; but so too are the details of 6 million customers who bought beauty products from Debenhams and the 1.4 million members of its Beauty Club loyalty scheme. boohoo has definite ambitions to expand its share of the beauty market, and it plans to leverage these new assets to help it do that.

The Laura Ashley story has a slightly different twist. It was bought by US ‘brand rescue’ company Gordon Brothers almost a year ago; in October 2020, Gordon Brothers announced it had signed a deal with Next which will see the latter launch a range of Laura Ashley products in its UK High Street stores and online in Spring 2021.

Significantly, Gordon Brothers’ deal for Laura Ashley included the company’s extensive design archives. Gordon Brothers made it clear that IP licensing was a major factor in the transaction. At the time of its demise, Laura Ashley had around 70 licensees worldwide selling a range of products, and Gordon Brothers plans to expand the number of licensees, so generating even more income from the IP.

The global retail industry was already in the middle of a drawn-out and painful transformation, as the rise of online shopping undercut the traditional retail business model. Reliance on bricks-and-mortar stores, either owned or occupied on relatively inflexible leases, was already an Achilles’ heel, as e-commerce slashed entry costs for new, more nimble rivals.

COVID-19 and lockdown have served to accelerate an already unstoppable process; shoppers were already abandoning bricks-and-mortar stores in favour of buying online. It has, tragically, meant many thousands of retail workers have lost their jobs; but, although little comfort to the people now out of work, the brands, and associated IP and intangible asset values, live on.

Martin Croft

Online retailer boohoo, which had already acquired the Debenhams brand intellectual property (IP) in January for £55m, has now picked up Burtons, Dorothy Perkins and Wallis brands from Arcadia for another £25m.

This follows last week’s news that rival online retailer ASOS has bought the Topshop, Topman, Miss Selfridge and sports brand HIIT, also from the bankrupt Arcadia Group.

ASOS paid £265m for the intellectual property and intangible assets, plus £30m for stock, so the brands can continue trading in the short term until they are integrated into the ASOS manufacturing and supply chain.

Neither boohoo nor ASOS are buying any of the relevant brands’ bricks and mortar retail outlets.

These deals ram home the fact that IP and intangible asset values – trade marks, copyrights, customer databases, designs, know-how, supplier relationships and the like – are now more important to companies than traditional tangible assets such as shops, warehouses, office buildings, stock, raw materials and vehicles.

As Inngot CEO Martin Brassell says: “IP and intangibles are valuable because of their uniqueness, and the ASOS and boohoo deals prove once again that worthwhile value can survive administration. In fact, IP and intangibles may be the only value that endures - the tangible assets these retail brands own, in particular the shops themselves, are much less in demand."

The value of IP when companies get into financial difficulties has become a key issue for lenders, particularly in the retail world. Its assessment is made more problematic by accounting rules that do not reflect the rise of brand valueand technology-related assets. Unless they have bought in the IP in question, companies are restricted in how they can recognise intangible assets on their balance sheet compared with physical, tangible assets.

Even where identifiable, internally-generated IP and intangibles do appear on company balance sheets, these entries are only at cost, and are required to be amortised (written off over time), so their value always appears to be in decline. In the real world, the opposite is often happening.

The fact that ASOS, boohoo and other purchasers are prepared to pay substantial amounts for collapsed retailers’ IP and intangibles shows they think these assets have real value, even as a “gone concern”, whatever the balance sheet may say – or rather, not say.

BooHoo’s purchase of the Debenhams brand and related intangibles is a good example of where the value now lies. Debenhams’ trade marks, designs and copyrights are certainly going to be of value to boohoo; but so too are the details of 6 million customers who bought beauty products from Debenhams and the 1.4 million members of its Beauty Club loyalty scheme. boohoo has definite ambitions to expand its share of the beauty market, and it plans to leverage these new assets to help it do that.

The Laura Ashley story has a slightly different twist. It was bought by US ‘brand rescue’ company Gordon Brothers almost a year ago; in October 2020, Gordon Brothers announced it had signed a deal with Next which will see the latter launch a range of Laura Ashley products in its UK High Street stores and online in Spring 2021.

Significantly, Gordon Brothers’ deal for Laura Ashley included the company’s extensive design archives. Gordon Brothers made it clear that IP licensing was a major factor in the transaction. At the time of its demise, Laura Ashley had around 70 licensees worldwide selling a range of products, and Gordon Brothers plans to expand the number of licensees, so generating even more income from the IP.

The global retail industry was already in the middle of a drawn-out and painful transformation, as the rise of online shopping undercut the traditional retail business model. Reliance on bricks-and-mortar stores, either owned or occupied on relatively inflexible leases, was already an Achilles’ heel, as e-commerce slashed entry costs for new, more nimble rivals.

COVID-19 and lockdown have served to accelerate an already unstoppable process; shoppers were already abandoning bricks-and-mortar stores in favour of buying online. It has, tragically, meant many thousands of retail workers have lost their jobs; but, although little comfort to the people now out of work, the brands, and associated IP and intangible asset values, live on.

Martin Croft

Online retailer boohoo, which had already acquired the Debenhams brand intellectual property (IP) in January for £55m, has now picked up Burtons, Dorothy Perkins and Wallis brands from Arcadia for another £25m.

This follows last week’s news that rival online retailer ASOS has bought the Topshop, Topman, Miss Selfridge and sports brand HIIT, also from the bankrupt Arcadia Group.

ASOS paid £265m for the intellectual property and intangible assets, plus £30m for stock, so the brands can continue trading in the short term until they are integrated into the ASOS manufacturing and supply chain.

Neither boohoo nor ASOS are buying any of the relevant brands’ bricks and mortar retail outlets.

These deals ram home the fact that IP and intangible asset values – trade marks, copyrights, customer databases, designs, know-how, supplier relationships and the like – are now more important to companies than traditional tangible assets such as shops, warehouses, office buildings, stock, raw materials and vehicles.

As Inngot CEO Martin Brassell says: “IP and intangibles are valuable because of their uniqueness, and the ASOS and boohoo deals prove once again that worthwhile value can survive administration. In fact, IP and intangibles may be the only value that endures - the tangible assets these retail brands own, in particular the shops themselves, are much less in demand."

The value of IP when companies get into financial difficulties has become a key issue for lenders, particularly in the retail world. Its assessment is made more problematic by accounting rules that do not reflect the rise of brand valueand technology-related assets. Unless they have bought in the IP in question, companies are restricted in how they can recognise intangible assets on their balance sheet compared with physical, tangible assets.

Even where identifiable, internally-generated IP and intangibles do appear on company balance sheets, these entries are only at cost, and are required to be amortised (written off over time), so their value always appears to be in decline. In the real world, the opposite is often happening.

The fact that ASOS, boohoo and other purchasers are prepared to pay substantial amounts for collapsed retailers’ IP and intangibles shows they think these assets have real value, even as a “gone concern”, whatever the balance sheet may say – or rather, not say.

BooHoo’s purchase of the Debenhams brand and related intangibles is a good example of where the value now lies. Debenhams’ trade marks, designs and copyrights are certainly going to be of value to boohoo; but so too are the details of 6 million customers who bought beauty products from Debenhams and the 1.4 million members of its Beauty Club loyalty scheme. boohoo has definite ambitions to expand its share of the beauty market, and it plans to leverage these new assets to help it do that.

The Laura Ashley story has a slightly different twist. It was bought by US ‘brand rescue’ company Gordon Brothers almost a year ago; in October 2020, Gordon Brothers announced it had signed a deal with Next which will see the latter launch a range of Laura Ashley products in its UK High Street stores and online in Spring 2021.

Significantly, Gordon Brothers’ deal for Laura Ashley included the company’s extensive design archives. Gordon Brothers made it clear that IP licensing was a major factor in the transaction. At the time of its demise, Laura Ashley had around 70 licensees worldwide selling a range of products, and Gordon Brothers plans to expand the number of licensees, so generating even more income from the IP.

The global retail industry was already in the middle of a drawn-out and painful transformation, as the rise of online shopping undercut the traditional retail business model. Reliance on bricks-and-mortar stores, either owned or occupied on relatively inflexible leases, was already an Achilles’ heel, as e-commerce slashed entry costs for new, more nimble rivals.

COVID-19 and lockdown have served to accelerate an already unstoppable process; shoppers were already abandoning bricks-and-mortar stores in favour of buying online. It has, tragically, meant many thousands of retail workers have lost their jobs; but, although little comfort to the people now out of work, the brands, and associated IP and intangible asset values, live on.

Martin Croft

Read Recent Articles

Inngot's online platform identifies all your intangible assets and demonstrates their value to lenders, investors, acquirers, licensees and stakeholders

Accreditations

Copyright © Inngot Limited 2019-2025. All rights reserved.

Inngot's online platform identifies all your intangible assets and demonstrates their value to lenders, investors, acquirers, licensees and stakeholders

Accreditations

Copyright © Inngot Limited 2019-2025. All rights reserved.

Inngot's online platform identifies all your intangible assets and demonstrates their value to lenders, investors, acquirers, licensees and stakeholders

Accreditations

Copyright © Inngot Limited 2019-2025. All rights reserved.

Inngot's online platform identifies all your intangible assets and demonstrates their value to lenders, investors, acquirers, licensees and stakeholders

Accreditations

Copyright © Inngot Limited 2019-2025. All rights reserved.