IP value – what’s the big deal?

20 May 2024

When I was a teenager, growing up in the Midlands in the 1970s, my home city was a major centre of industrial production. I lived a short walk from the old Standard Triumph engineering factory (then part of British Leyland) and worked on a milk round, before going to school.

Every day I’d deliver bottles or crates of milk to just a handful of the thousands of small engineering companies that could be found on almost every street and whose dark, oily-smelling premises hummed and clanked, as they produced the thousands of components needed for every type of industrial application.

Then, later in the day, my bus home from school would frequently be held up, as hundreds of workers streamed out of ‘The Standard’ factory gates to make their way home.

This memory of 1970s industrial Britain evokes in my mind an age of machinery and other tangible goods that the UK churned-out 24/7 and shipped to all corners of the globe, creating value for the companies, their shareholders and workers, as well as for the UK as a whole.

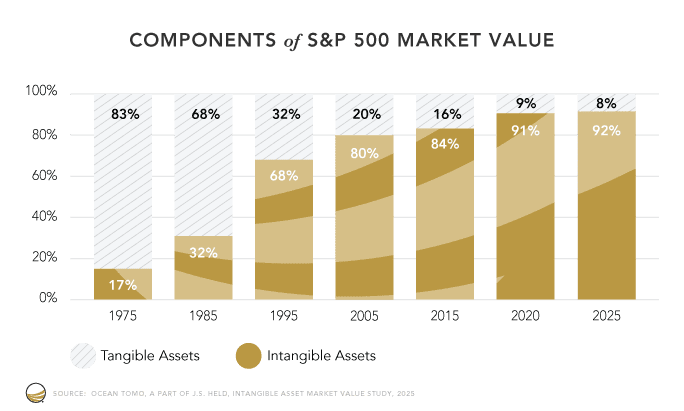

In those days, when reviewing the balance sheets of most companies, a huge amount of value often existed in the company’s tangible assets, such as their buildings, the machinery and equipment they used to make things, as well as in raw material stocks, work in progress and finished goods. In fact, it wasn’t uncommon to see over 80% of a firm’s value locked up in their tangible assets, with intangibles accounting for very little.

However, all this began to change during the 1980s, as the introduction of new information and communications technologies enabled firms to do away with the old, analogue methods of manufacturing.

Computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) gradually replaced large numbers of specialist machines, with fewer, smaller and more versatile machines; computer-based systems began to enable real-time inventory management and these, combined with just-in-time raw material scheduling, enabled organisations to all but eliminate raw material stock holding.

As this technology reduced manufacturing timescales, inventories of part-finished and finished goods stock also declined, further reducing the value of tangible assets on many organisations’ balance sheets.

Then, towards the end of the decade, personal computing technology flooded into even the smallest businesses, bringing productivity boosts that were further enhanced, just a few, short years later, by the internet, email, and mobile communications devices.

So, today, while there are still a considerable number of organisations out there with large tangible asset values on their balance sheets, on average, the tangible-intangible ratio has ‘flipped’ and for some firms over 90% of an organisation’s value can now be attributed to intangible assets and intellectual property (IP).

This is not surprising in an age when the old Standard Triumph factory is now the site of a business park and those small, dark engineering companies have long gone, replaced by sheltered housing complexes and community centres. We now live in an era when a couple of people, working from a spare bedroom with some fairly simple technology, can develop a piece of software worth many millions of pounds.

And the percentage of company value attributable to IP, edges ever higher – but how can we work out the value of our IP?

First, it’d be good to start with an example that everyone can relate to.

Valuing a tangible asset has always been a fairly straightforward affair: if you have a building you can compare it with other similar buildings; and the same is true of vehicles, machinery and other physical assets. This is because there is an established, mature market for most (if not all) tangible goods and the values of such goods are determined by a number of factors, including supply and demand, quality, etc.

This method of valuing goods is referred to as the market-based valuation method. So, for example, if you are a factory owner with a piece of machinery, you can use this method to work out its value, stick it on the balance sheet and allow for it wearing out by ‘depreciating’ its value over a number of years.

Unfortunately, the same is not (generally) true for IP and other intangibles, so, while a market-based approach can be taken to valuing IP, it is often constrained by a number of factors, including the likelihood that there may not be an established or mature market for the IP, as well as the fact that most IP, by its very nature, is unique; in other words, it is often very difficult, if not impossible, to compare ‘like with like’.

So what other valuation options do we have? Some of you may have worked out that we could use a cost-based approach. This is where all the costs associated with creating the IP are calculated to derive a value, much in the same way as a manufacturer of plant pots might establish a price for their products.

Unfortunately, the cost-based method is often not reflective of the true value of the IP, as it may have cost a lot to develop, but is commercially hopeless, or – ideally – it has cost very little to develop, but has huge commercial potential.

A good example of this would be the relatively low development costs of the original Coca-Cola soft drink formula, which may have only cost a few hundreds or thousands of dollars to develop; but Coca-Cola has now become one of the most widely recognised global soft drink brands (albeit with a lot more subsequent investment in marketing, branding and product development).

Finally, we have the income-based IP valuation approach, which is a more complex method that uses the anticipated income attributable to the IP over its useful lifetime, along with relief from royalty, cost of money and risk weighting calculations, to derive a current, indicative value range for the IP.

The income based valuation method is widely regarded as the most reliable and accurate way to value IP and this is especially true if it can be supported with any market-based valuation comparisons. As an example, at Inngot, our methodology has evolved to incorporate elements of all three methods and, without going into too much detail, let’s look at why we do that.

Probably the easiest way to think about it is to use a tangibles-based analogy. Think about a commercial building. The building can be sold or leased to an occupier, so it is capable of yielding an income (potentially over a long period of time) and there is a lot of value in that, but what about the cost of construction and fit-out, or the comparable market value of the completed building – don’t they also have a bearing on the ultimate value? In some respects it depends on who you are: if you are the person who has built it with the intention of leasing it to an occupier, the answer to that question is, almost certainly, yes; if you are the person financing the build or providing a mortgage, again, probably yes. What about the person who intends to buy the building or occupy it – do they care about anything more than how much they have to pay to acquire or use the building? Possibly. Obviously, in lots of cases, it is good to have a comprehensive understanding of the value of the asset in the broadest sense and we recognise that different organisations have different reasons for wanting to know the value of IP. So, hopefully, this example helps to explain why a triangulated view of IP value may be more useful than a single, one-dimensional approach.

So that’s it. Almost.

There is one final ‘sense-check’ we include and that is to combine everything into a single, orderly disposal value which indicates how much the IP could be marketed at, if it were to be sold as a ‘going concern’. As with our example, above, knowing the orderly disposal value is a starting point for working out the collateral value of the asset and, with IP-backed lending now helping to drive business growth throughout the UK, this is a vital element in transforming IP valuation into ‘big deals’.

For more exciting news about how Inngot’s services are helping to drive business growth pop over to our Case studies or News and views pages.

When I was a teenager, growing up in the Midlands in the 1970s, my home city was a major centre of industrial production. I lived a short walk from the old Standard Triumph engineering factory (then part of British Leyland) and worked on a milk round, before going to school.

Every day I’d deliver bottles or crates of milk to just a handful of the thousands of small engineering companies that could be found on almost every street and whose dark, oily-smelling premises hummed and clanked, as they produced the thousands of components needed for every type of industrial application.

Then, later in the day, my bus home from school would frequently be held up, as hundreds of workers streamed out of ‘The Standard’ factory gates to make their way home.

This memory of 1970s industrial Britain evokes in my mind an age of machinery and other tangible goods that the UK churned-out 24/7 and shipped to all corners of the globe, creating value for the companies, their shareholders and workers, as well as for the UK as a whole.

In those days, when reviewing the balance sheets of most companies, a huge amount of value often existed in the company’s tangible assets, such as their buildings, the machinery and equipment they used to make things, as well as in raw material stocks, work in progress and finished goods. In fact, it wasn’t uncommon to see over 80% of a firm’s value locked up in their tangible assets, with intangibles accounting for very little.

However, all this began to change during the 1980s, as the introduction of new information and communications technologies enabled firms to do away with the old, analogue methods of manufacturing.

Computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) gradually replaced large numbers of specialist machines, with fewer, smaller and more versatile machines; computer-based systems began to enable real-time inventory management and these, combined with just-in-time raw material scheduling, enabled organisations to all but eliminate raw material stock holding.

As this technology reduced manufacturing timescales, inventories of part-finished and finished goods stock also declined, further reducing the value of tangible assets on many organisations’ balance sheets.

Then, towards the end of the decade, personal computing technology flooded into even the smallest businesses, bringing productivity boosts that were further enhanced, just a few, short years later, by the internet, email, and mobile communications devices.

So, today, while there are still a considerable number of organisations out there with large tangible asset values on their balance sheets, on average, the tangible-intangible ratio has ‘flipped’ and for some firms over 90% of an organisation’s value can now be attributed to intangible assets and intellectual property (IP).

This is not surprising in an age when the old Standard Triumph factory is now the site of a business park and those small, dark engineering companies have long gone, replaced by sheltered housing complexes and community centres. We now live in an era when a couple of people, working from a spare bedroom with some fairly simple technology, can develop a piece of software worth many millions of pounds.

And the percentage of company value attributable to IP, edges ever higher – but how can we work out the value of our IP?

First, it’d be good to start with an example that everyone can relate to.

Valuing a tangible asset has always been a fairly straightforward affair: if you have a building you can compare it with other similar buildings; and the same is true of vehicles, machinery and other physical assets. This is because there is an established, mature market for most (if not all) tangible goods and the values of such goods are determined by a number of factors, including supply and demand, quality, etc.

This method of valuing goods is referred to as the market-based valuation method. So, for example, if you are a factory owner with a piece of machinery, you can use this method to work out its value, stick it on the balance sheet and allow for it wearing out by ‘depreciating’ its value over a number of years.

Unfortunately, the same is not (generally) true for IP and other intangibles, so, while a market-based approach can be taken to valuing IP, it is often constrained by a number of factors, including the likelihood that there may not be an established or mature market for the IP, as well as the fact that most IP, by its very nature, is unique; in other words, it is often very difficult, if not impossible, to compare ‘like with like’.

So what other valuation options do we have? Some of you may have worked out that we could use a cost-based approach. This is where all the costs associated with creating the IP are calculated to derive a value, much in the same way as a manufacturer of plant pots might establish a price for their products.

Unfortunately, the cost-based method is often not reflective of the true value of the IP, as it may have cost a lot to develop, but is commercially hopeless, or – ideally – it has cost very little to develop, but has huge commercial potential.

A good example of this would be the relatively low development costs of the original Coca-Cola soft drink formula, which may have only cost a few hundreds or thousands of dollars to develop; but Coca-Cola has now become one of the most widely recognised global soft drink brands (albeit with a lot more subsequent investment in marketing, branding and product development).

Finally, we have the income-based IP valuation approach, which is a more complex method that uses the anticipated income attributable to the IP over its useful lifetime, along with relief from royalty, cost of money and risk weighting calculations, to derive a current, indicative value range for the IP.

The income based valuation method is widely regarded as the most reliable and accurate way to value IP and this is especially true if it can be supported with any market-based valuation comparisons. As an example, at Inngot, our methodology has evolved to incorporate elements of all three methods and, without going into too much detail, let’s look at why we do that.

Probably the easiest way to think about it is to use a tangibles-based analogy. Think about a commercial building. The building can be sold or leased to an occupier, so it is capable of yielding an income (potentially over a long period of time) and there is a lot of value in that, but what about the cost of construction and fit-out, or the comparable market value of the completed building – don’t they also have a bearing on the ultimate value? In some respects it depends on who you are: if you are the person who has built it with the intention of leasing it to an occupier, the answer to that question is, almost certainly, yes; if you are the person financing the build or providing a mortgage, again, probably yes. What about the person who intends to buy the building or occupy it – do they care about anything more than how much they have to pay to acquire or use the building? Possibly. Obviously, in lots of cases, it is good to have a comprehensive understanding of the value of the asset in the broadest sense and we recognise that different organisations have different reasons for wanting to know the value of IP. So, hopefully, this example helps to explain why a triangulated view of IP value may be more useful than a single, one-dimensional approach.

So that’s it. Almost.

There is one final ‘sense-check’ we include and that is to combine everything into a single, orderly disposal value which indicates how much the IP could be marketed at, if it were to be sold as a ‘going concern’. As with our example, above, knowing the orderly disposal value is a starting point for working out the collateral value of the asset and, with IP-backed lending now helping to drive business growth throughout the UK, this is a vital element in transforming IP valuation into ‘big deals’.

For more exciting news about how Inngot’s services are helping to drive business growth pop over to our Case studies or News and views pages.

When I was a teenager, growing up in the Midlands in the 1970s, my home city was a major centre of industrial production. I lived a short walk from the old Standard Triumph engineering factory (then part of British Leyland) and worked on a milk round, before going to school.

Every day I’d deliver bottles or crates of milk to just a handful of the thousands of small engineering companies that could be found on almost every street and whose dark, oily-smelling premises hummed and clanked, as they produced the thousands of components needed for every type of industrial application.

Then, later in the day, my bus home from school would frequently be held up, as hundreds of workers streamed out of ‘The Standard’ factory gates to make their way home.

This memory of 1970s industrial Britain evokes in my mind an age of machinery and other tangible goods that the UK churned-out 24/7 and shipped to all corners of the globe, creating value for the companies, their shareholders and workers, as well as for the UK as a whole.

In those days, when reviewing the balance sheets of most companies, a huge amount of value often existed in the company’s tangible assets, such as their buildings, the machinery and equipment they used to make things, as well as in raw material stocks, work in progress and finished goods. In fact, it wasn’t uncommon to see over 80% of a firm’s value locked up in their tangible assets, with intangibles accounting for very little.

However, all this began to change during the 1980s, as the introduction of new information and communications technologies enabled firms to do away with the old, analogue methods of manufacturing.

Computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) gradually replaced large numbers of specialist machines, with fewer, smaller and more versatile machines; computer-based systems began to enable real-time inventory management and these, combined with just-in-time raw material scheduling, enabled organisations to all but eliminate raw material stock holding.

As this technology reduced manufacturing timescales, inventories of part-finished and finished goods stock also declined, further reducing the value of tangible assets on many organisations’ balance sheets.

Then, towards the end of the decade, personal computing technology flooded into even the smallest businesses, bringing productivity boosts that were further enhanced, just a few, short years later, by the internet, email, and mobile communications devices.

So, today, while there are still a considerable number of organisations out there with large tangible asset values on their balance sheets, on average, the tangible-intangible ratio has ‘flipped’ and for some firms over 90% of an organisation’s value can now be attributed to intangible assets and intellectual property (IP).

This is not surprising in an age when the old Standard Triumph factory is now the site of a business park and those small, dark engineering companies have long gone, replaced by sheltered housing complexes and community centres. We now live in an era when a couple of people, working from a spare bedroom with some fairly simple technology, can develop a piece of software worth many millions of pounds.

And the percentage of company value attributable to IP, edges ever higher – but how can we work out the value of our IP?

First, it’d be good to start with an example that everyone can relate to.

Valuing a tangible asset has always been a fairly straightforward affair: if you have a building you can compare it with other similar buildings; and the same is true of vehicles, machinery and other physical assets. This is because there is an established, mature market for most (if not all) tangible goods and the values of such goods are determined by a number of factors, including supply and demand, quality, etc.

This method of valuing goods is referred to as the market-based valuation method. So, for example, if you are a factory owner with a piece of machinery, you can use this method to work out its value, stick it on the balance sheet and allow for it wearing out by ‘depreciating’ its value over a number of years.

Unfortunately, the same is not (generally) true for IP and other intangibles, so, while a market-based approach can be taken to valuing IP, it is often constrained by a number of factors, including the likelihood that there may not be an established or mature market for the IP, as well as the fact that most IP, by its very nature, is unique; in other words, it is often very difficult, if not impossible, to compare ‘like with like’.

So what other valuation options do we have? Some of you may have worked out that we could use a cost-based approach. This is where all the costs associated with creating the IP are calculated to derive a value, much in the same way as a manufacturer of plant pots might establish a price for their products.

Unfortunately, the cost-based method is often not reflective of the true value of the IP, as it may have cost a lot to develop, but is commercially hopeless, or – ideally – it has cost very little to develop, but has huge commercial potential.

A good example of this would be the relatively low development costs of the original Coca-Cola soft drink formula, which may have only cost a few hundreds or thousands of dollars to develop; but Coca-Cola has now become one of the most widely recognised global soft drink brands (albeit with a lot more subsequent investment in marketing, branding and product development).

Finally, we have the income-based IP valuation approach, which is a more complex method that uses the anticipated income attributable to the IP over its useful lifetime, along with relief from royalty, cost of money and risk weighting calculations, to derive a current, indicative value range for the IP.

The income based valuation method is widely regarded as the most reliable and accurate way to value IP and this is especially true if it can be supported with any market-based valuation comparisons. As an example, at Inngot, our methodology has evolved to incorporate elements of all three methods and, without going into too much detail, let’s look at why we do that.

Probably the easiest way to think about it is to use a tangibles-based analogy. Think about a commercial building. The building can be sold or leased to an occupier, so it is capable of yielding an income (potentially over a long period of time) and there is a lot of value in that, but what about the cost of construction and fit-out, or the comparable market value of the completed building – don’t they also have a bearing on the ultimate value? In some respects it depends on who you are: if you are the person who has built it with the intention of leasing it to an occupier, the answer to that question is, almost certainly, yes; if you are the person financing the build or providing a mortgage, again, probably yes. What about the person who intends to buy the building or occupy it – do they care about anything more than how much they have to pay to acquire or use the building? Possibly. Obviously, in lots of cases, it is good to have a comprehensive understanding of the value of the asset in the broadest sense and we recognise that different organisations have different reasons for wanting to know the value of IP. So, hopefully, this example helps to explain why a triangulated view of IP value may be more useful than a single, one-dimensional approach.

So that’s it. Almost.

There is one final ‘sense-check’ we include and that is to combine everything into a single, orderly disposal value which indicates how much the IP could be marketed at, if it were to be sold as a ‘going concern’. As with our example, above, knowing the orderly disposal value is a starting point for working out the collateral value of the asset and, with IP-backed lending now helping to drive business growth throughout the UK, this is a vital element in transforming IP valuation into ‘big deals’.

For more exciting news about how Inngot’s services are helping to drive business growth pop over to our Case studies or News and views pages.

When I was a teenager, growing up in the Midlands in the 1970s, my home city was a major centre of industrial production. I lived a short walk from the old Standard Triumph engineering factory (then part of British Leyland) and worked on a milk round, before going to school.

Every day I’d deliver bottles or crates of milk to just a handful of the thousands of small engineering companies that could be found on almost every street and whose dark, oily-smelling premises hummed and clanked, as they produced the thousands of components needed for every type of industrial application.

Then, later in the day, my bus home from school would frequently be held up, as hundreds of workers streamed out of ‘The Standard’ factory gates to make their way home.

This memory of 1970s industrial Britain evokes in my mind an age of machinery and other tangible goods that the UK churned-out 24/7 and shipped to all corners of the globe, creating value for the companies, their shareholders and workers, as well as for the UK as a whole.

In those days, when reviewing the balance sheets of most companies, a huge amount of value often existed in the company’s tangible assets, such as their buildings, the machinery and equipment they used to make things, as well as in raw material stocks, work in progress and finished goods. In fact, it wasn’t uncommon to see over 80% of a firm’s value locked up in their tangible assets, with intangibles accounting for very little.

However, all this began to change during the 1980s, as the introduction of new information and communications technologies enabled firms to do away with the old, analogue methods of manufacturing.

Computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) gradually replaced large numbers of specialist machines, with fewer, smaller and more versatile machines; computer-based systems began to enable real-time inventory management and these, combined with just-in-time raw material scheduling, enabled organisations to all but eliminate raw material stock holding.

As this technology reduced manufacturing timescales, inventories of part-finished and finished goods stock also declined, further reducing the value of tangible assets on many organisations’ balance sheets.

Then, towards the end of the decade, personal computing technology flooded into even the smallest businesses, bringing productivity boosts that were further enhanced, just a few, short years later, by the internet, email, and mobile communications devices.

So, today, while there are still a considerable number of organisations out there with large tangible asset values on their balance sheets, on average, the tangible-intangible ratio has ‘flipped’ and for some firms over 90% of an organisation’s value can now be attributed to intangible assets and intellectual property (IP).

This is not surprising in an age when the old Standard Triumph factory is now the site of a business park and those small, dark engineering companies have long gone, replaced by sheltered housing complexes and community centres. We now live in an era when a couple of people, working from a spare bedroom with some fairly simple technology, can develop a piece of software worth many millions of pounds.

And the percentage of company value attributable to IP, edges ever higher – but how can we work out the value of our IP?

First, it’d be good to start with an example that everyone can relate to.

Valuing a tangible asset has always been a fairly straightforward affair: if you have a building you can compare it with other similar buildings; and the same is true of vehicles, machinery and other physical assets. This is because there is an established, mature market for most (if not all) tangible goods and the values of such goods are determined by a number of factors, including supply and demand, quality, etc.

This method of valuing goods is referred to as the market-based valuation method. So, for example, if you are a factory owner with a piece of machinery, you can use this method to work out its value, stick it on the balance sheet and allow for it wearing out by ‘depreciating’ its value over a number of years.

Unfortunately, the same is not (generally) true for IP and other intangibles, so, while a market-based approach can be taken to valuing IP, it is often constrained by a number of factors, including the likelihood that there may not be an established or mature market for the IP, as well as the fact that most IP, by its very nature, is unique; in other words, it is often very difficult, if not impossible, to compare ‘like with like’.

So what other valuation options do we have? Some of you may have worked out that we could use a cost-based approach. This is where all the costs associated with creating the IP are calculated to derive a value, much in the same way as a manufacturer of plant pots might establish a price for their products.

Unfortunately, the cost-based method is often not reflective of the true value of the IP, as it may have cost a lot to develop, but is commercially hopeless, or – ideally – it has cost very little to develop, but has huge commercial potential.

A good example of this would be the relatively low development costs of the original Coca-Cola soft drink formula, which may have only cost a few hundreds or thousands of dollars to develop; but Coca-Cola has now become one of the most widely recognised global soft drink brands (albeit with a lot more subsequent investment in marketing, branding and product development).

Finally, we have the income-based IP valuation approach, which is a more complex method that uses the anticipated income attributable to the IP over its useful lifetime, along with relief from royalty, cost of money and risk weighting calculations, to derive a current, indicative value range for the IP.

The income based valuation method is widely regarded as the most reliable and accurate way to value IP and this is especially true if it can be supported with any market-based valuation comparisons. As an example, at Inngot, our methodology has evolved to incorporate elements of all three methods and, without going into too much detail, let’s look at why we do that.

Probably the easiest way to think about it is to use a tangibles-based analogy. Think about a commercial building. The building can be sold or leased to an occupier, so it is capable of yielding an income (potentially over a long period of time) and there is a lot of value in that, but what about the cost of construction and fit-out, or the comparable market value of the completed building – don’t they also have a bearing on the ultimate value? In some respects it depends on who you are: if you are the person who has built it with the intention of leasing it to an occupier, the answer to that question is, almost certainly, yes; if you are the person financing the build or providing a mortgage, again, probably yes. What about the person who intends to buy the building or occupy it – do they care about anything more than how much they have to pay to acquire or use the building? Possibly. Obviously, in lots of cases, it is good to have a comprehensive understanding of the value of the asset in the broadest sense and we recognise that different organisations have different reasons for wanting to know the value of IP. So, hopefully, this example helps to explain why a triangulated view of IP value may be more useful than a single, one-dimensional approach.

So that’s it. Almost.

There is one final ‘sense-check’ we include and that is to combine everything into a single, orderly disposal value which indicates how much the IP could be marketed at, if it were to be sold as a ‘going concern’. As with our example, above, knowing the orderly disposal value is a starting point for working out the collateral value of the asset and, with IP-backed lending now helping to drive business growth throughout the UK, this is a vital element in transforming IP valuation into ‘big deals’.

For more exciting news about how Inngot’s services are helping to drive business growth pop over to our Case studies or News and views pages.

Read Recent Articles

Inngot's online platform identifies all your intangible assets and demonstrates their value to lenders, investors, acquirers, licensees and stakeholders

Accreditations

Copyright © Inngot Limited 2019-2025. All rights reserved.

Inngot's online platform identifies all your intangible assets and demonstrates their value to lenders, investors, acquirers, licensees and stakeholders

Accreditations

Copyright © Inngot Limited 2019-2025. All rights reserved.

Inngot's online platform identifies all your intangible assets and demonstrates their value to lenders, investors, acquirers, licensees and stakeholders

Accreditations

Copyright © Inngot Limited 2019-2025. All rights reserved.

Inngot's online platform identifies all your intangible assets and demonstrates their value to lenders, investors, acquirers, licensees and stakeholders

Accreditations

Copyright © Inngot Limited 2019-2025. All rights reserved.