The EU AI Act and copyright

10 Feb 2025

Strict new rules on certain uses of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools came into force in the European Union as of February 2nd, 2025 as the first elements of the EU’s new AI Act kicked in – despite warnings from US President Donald Trump over the possibility of fines for US companies which may be found to be breaking the new rules.

The full AI Act is supposed to come into force on August 2nd, 2026; but as of the beginning of February this year, a number of practices have been banned.

These include:

AI-enabled dark patterns embedded in services. Dark patterns, the EU says, are 'tricks used in websites and apps that make you do things that you didn't mean to, like buying or signing up for something', based on harmful online choice architecture.

AI-enabled applications which exploit users based on their age, disability or socio-economic situation.

AI-enabled social scoring using unrelated personal data such as origin and race by social welfare agencies and other public and private bodies is banned

Police are not allowed to predict individuals' criminal behaviour solely based on their biometric data if this has not been verified.

Employers cannot use webcams and voice recognition systems to track employees' emotions.

The use of AI-based facial recognition technologies, particularly if they involved scraping the Internet or CCTV cameras, is banned. But there are exceptions for legitimate law enforcement-related activities, like real-time facial recognition in public spaces or as an aid in assessing a suspect's participation in a crime.

Emotional detection technology in schools and workplace.

Any company found to be using AI for these restricted purposes in the EU faces a fine of up to 35 million euros or 7% of their annual global revenue, whichever is higher. When the full Act comes into force, there will be other, lower, fines for breaking a range of other rules.

Copyright and the new AI Act

However, from the IP point of view, the most interesting element of the new AI Act when it fully comes into force will be the requirement for AI developers to respect copyright laws when training AI and Machine Learning models and when conducting Text and Data Mining (TDM).

Using copyright materials in training will usually require a licence from the copyright holder. There are certain exceptions for scientific research, which apply to both public and commercial bodies; but copyright holders will have the right to opt-out of these exceptions, refusing to allow their data to be mined for TDM .

There are varying levels of obligation under the new act, depending on where a company fits into the AI ‘distribution chain. The EU has created a hierarchy of roles within this chain, and some parts of the Act will apply to all of these roles.

However, the main restrictions seem to apply to a company that actually creates an AI system (defined under the Act as a Provider).

Focusing again on IP, the Provider of a system must collate and make public a “sufficiently detailed summary” of the data used to train its model. This is so anyone with a legitimate interest – such as a privacy or data regulator or a copyright holder – can better understand whether private, personal data or copyright material was used during training.

As yet, how detailed such a summary will have to be, and how people will be able to access it, is unclear.

However, the EU AI Act is what is called “maximum harmonisation” – this means EU member states must enact it as it stands. They cannot pass laws that are more restrictive than the rules laid out in the AI Act. This is to ensure that the laws governing AI are the same across the EU. That may sound obvious; but some EU laws are “minimum harmonisations”, which means laws can be stricter in one country than another.

The EU AI Act will also be applicable to companies based outside the EU but whose AI products are used within the EU, or which use someone else’s AI systems. It is this point which Donald Trump has apparently taken issue with, suggesting it is a tax on US tech companies.

Any UK company which plans to use AI, and which does business in the EU, should take advice on what its obligations are under the new Act. It may also be worthwhile for UK copyright owners to monitor the summaries of copyright materials used to train AI systems which are eventually published.

Strict new rules on certain uses of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools came into force in the European Union as of February 2nd, 2025 as the first elements of the EU’s new AI Act kicked in – despite warnings from US President Donald Trump over the possibility of fines for US companies which may be found to be breaking the new rules.

The full AI Act is supposed to come into force on August 2nd, 2026; but as of the beginning of February this year, a number of practices have been banned.

These include:

AI-enabled dark patterns embedded in services. Dark patterns, the EU says, are 'tricks used in websites and apps that make you do things that you didn't mean to, like buying or signing up for something', based on harmful online choice architecture.

AI-enabled applications which exploit users based on their age, disability or socio-economic situation.

AI-enabled social scoring using unrelated personal data such as origin and race by social welfare agencies and other public and private bodies is banned

Police are not allowed to predict individuals' criminal behaviour solely based on their biometric data if this has not been verified.

Employers cannot use webcams and voice recognition systems to track employees' emotions.

The use of AI-based facial recognition technologies, particularly if they involved scraping the Internet or CCTV cameras, is banned. But there are exceptions for legitimate law enforcement-related activities, like real-time facial recognition in public spaces or as an aid in assessing a suspect's participation in a crime.

Emotional detection technology in schools and workplace.

Any company found to be using AI for these restricted purposes in the EU faces a fine of up to 35 million euros or 7% of their annual global revenue, whichever is higher. When the full Act comes into force, there will be other, lower, fines for breaking a range of other rules.

Copyright and the new AI Act

However, from the IP point of view, the most interesting element of the new AI Act when it fully comes into force will be the requirement for AI developers to respect copyright laws when training AI and Machine Learning models and when conducting Text and Data Mining (TDM).

Using copyright materials in training will usually require a licence from the copyright holder. There are certain exceptions for scientific research, which apply to both public and commercial bodies; but copyright holders will have the right to opt-out of these exceptions, refusing to allow their data to be mined for TDM .

There are varying levels of obligation under the new act, depending on where a company fits into the AI ‘distribution chain. The EU has created a hierarchy of roles within this chain, and some parts of the Act will apply to all of these roles.

However, the main restrictions seem to apply to a company that actually creates an AI system (defined under the Act as a Provider).

Focusing again on IP, the Provider of a system must collate and make public a “sufficiently detailed summary” of the data used to train its model. This is so anyone with a legitimate interest – such as a privacy or data regulator or a copyright holder – can better understand whether private, personal data or copyright material was used during training.

As yet, how detailed such a summary will have to be, and how people will be able to access it, is unclear.

However, the EU AI Act is what is called “maximum harmonisation” – this means EU member states must enact it as it stands. They cannot pass laws that are more restrictive than the rules laid out in the AI Act. This is to ensure that the laws governing AI are the same across the EU. That may sound obvious; but some EU laws are “minimum harmonisations”, which means laws can be stricter in one country than another.

The EU AI Act will also be applicable to companies based outside the EU but whose AI products are used within the EU, or which use someone else’s AI systems. It is this point which Donald Trump has apparently taken issue with, suggesting it is a tax on US tech companies.

Any UK company which plans to use AI, and which does business in the EU, should take advice on what its obligations are under the new Act. It may also be worthwhile for UK copyright owners to monitor the summaries of copyright materials used to train AI systems which are eventually published.

Strict new rules on certain uses of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools came into force in the European Union as of February 2nd, 2025 as the first elements of the EU’s new AI Act kicked in – despite warnings from US President Donald Trump over the possibility of fines for US companies which may be found to be breaking the new rules.

The full AI Act is supposed to come into force on August 2nd, 2026; but as of the beginning of February this year, a number of practices have been banned.

These include:

AI-enabled dark patterns embedded in services. Dark patterns, the EU says, are 'tricks used in websites and apps that make you do things that you didn't mean to, like buying or signing up for something', based on harmful online choice architecture.

AI-enabled applications which exploit users based on their age, disability or socio-economic situation.

AI-enabled social scoring using unrelated personal data such as origin and race by social welfare agencies and other public and private bodies is banned

Police are not allowed to predict individuals' criminal behaviour solely based on their biometric data if this has not been verified.

Employers cannot use webcams and voice recognition systems to track employees' emotions.

The use of AI-based facial recognition technologies, particularly if they involved scraping the Internet or CCTV cameras, is banned. But there are exceptions for legitimate law enforcement-related activities, like real-time facial recognition in public spaces or as an aid in assessing a suspect's participation in a crime.

Emotional detection technology in schools and workplace.

Any company found to be using AI for these restricted purposes in the EU faces a fine of up to 35 million euros or 7% of their annual global revenue, whichever is higher. When the full Act comes into force, there will be other, lower, fines for breaking a range of other rules.

Copyright and the new AI Act

However, from the IP point of view, the most interesting element of the new AI Act when it fully comes into force will be the requirement for AI developers to respect copyright laws when training AI and Machine Learning models and when conducting Text and Data Mining (TDM).

Using copyright materials in training will usually require a licence from the copyright holder. There are certain exceptions for scientific research, which apply to both public and commercial bodies; but copyright holders will have the right to opt-out of these exceptions, refusing to allow their data to be mined for TDM .

There are varying levels of obligation under the new act, depending on where a company fits into the AI ‘distribution chain. The EU has created a hierarchy of roles within this chain, and some parts of the Act will apply to all of these roles.

However, the main restrictions seem to apply to a company that actually creates an AI system (defined under the Act as a Provider).

Focusing again on IP, the Provider of a system must collate and make public a “sufficiently detailed summary” of the data used to train its model. This is so anyone with a legitimate interest – such as a privacy or data regulator or a copyright holder – can better understand whether private, personal data or copyright material was used during training.

As yet, how detailed such a summary will have to be, and how people will be able to access it, is unclear.

However, the EU AI Act is what is called “maximum harmonisation” – this means EU member states must enact it as it stands. They cannot pass laws that are more restrictive than the rules laid out in the AI Act. This is to ensure that the laws governing AI are the same across the EU. That may sound obvious; but some EU laws are “minimum harmonisations”, which means laws can be stricter in one country than another.

The EU AI Act will also be applicable to companies based outside the EU but whose AI products are used within the EU, or which use someone else’s AI systems. It is this point which Donald Trump has apparently taken issue with, suggesting it is a tax on US tech companies.

Any UK company which plans to use AI, and which does business in the EU, should take advice on what its obligations are under the new Act. It may also be worthwhile for UK copyright owners to monitor the summaries of copyright materials used to train AI systems which are eventually published.

Strict new rules on certain uses of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools came into force in the European Union as of February 2nd, 2025 as the first elements of the EU’s new AI Act kicked in – despite warnings from US President Donald Trump over the possibility of fines for US companies which may be found to be breaking the new rules.

The full AI Act is supposed to come into force on August 2nd, 2026; but as of the beginning of February this year, a number of practices have been banned.

These include:

AI-enabled dark patterns embedded in services. Dark patterns, the EU says, are 'tricks used in websites and apps that make you do things that you didn't mean to, like buying or signing up for something', based on harmful online choice architecture.

AI-enabled applications which exploit users based on their age, disability or socio-economic situation.

AI-enabled social scoring using unrelated personal data such as origin and race by social welfare agencies and other public and private bodies is banned

Police are not allowed to predict individuals' criminal behaviour solely based on their biometric data if this has not been verified.

Employers cannot use webcams and voice recognition systems to track employees' emotions.

The use of AI-based facial recognition technologies, particularly if they involved scraping the Internet or CCTV cameras, is banned. But there are exceptions for legitimate law enforcement-related activities, like real-time facial recognition in public spaces or as an aid in assessing a suspect's participation in a crime.

Emotional detection technology in schools and workplace.

Any company found to be using AI for these restricted purposes in the EU faces a fine of up to 35 million euros or 7% of their annual global revenue, whichever is higher. When the full Act comes into force, there will be other, lower, fines for breaking a range of other rules.

Copyright and the new AI Act

However, from the IP point of view, the most interesting element of the new AI Act when it fully comes into force will be the requirement for AI developers to respect copyright laws when training AI and Machine Learning models and when conducting Text and Data Mining (TDM).

Using copyright materials in training will usually require a licence from the copyright holder. There are certain exceptions for scientific research, which apply to both public and commercial bodies; but copyright holders will have the right to opt-out of these exceptions, refusing to allow their data to be mined for TDM .

There are varying levels of obligation under the new act, depending on where a company fits into the AI ‘distribution chain. The EU has created a hierarchy of roles within this chain, and some parts of the Act will apply to all of these roles.

However, the main restrictions seem to apply to a company that actually creates an AI system (defined under the Act as a Provider).

Focusing again on IP, the Provider of a system must collate and make public a “sufficiently detailed summary” of the data used to train its model. This is so anyone with a legitimate interest – such as a privacy or data regulator or a copyright holder – can better understand whether private, personal data or copyright material was used during training.

As yet, how detailed such a summary will have to be, and how people will be able to access it, is unclear.

However, the EU AI Act is what is called “maximum harmonisation” – this means EU member states must enact it as it stands. They cannot pass laws that are more restrictive than the rules laid out in the AI Act. This is to ensure that the laws governing AI are the same across the EU. That may sound obvious; but some EU laws are “minimum harmonisations”, which means laws can be stricter in one country than another.

The EU AI Act will also be applicable to companies based outside the EU but whose AI products are used within the EU, or which use someone else’s AI systems. It is this point which Donald Trump has apparently taken issue with, suggesting it is a tax on US tech companies.

Any UK company which plans to use AI, and which does business in the EU, should take advice on what its obligations are under the new Act. It may also be worthwhile for UK copyright owners to monitor the summaries of copyright materials used to train AI systems which are eventually published.

Read Recent Articles

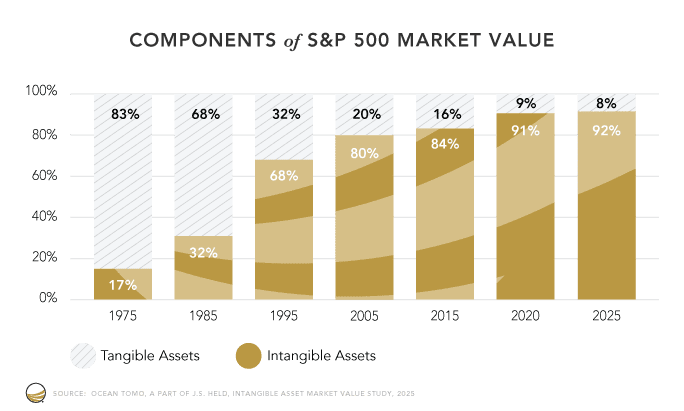

Inngot's online platform identifies all your intangible assets and demonstrates their value to lenders, investors, acquirers, licensees and stakeholders

Accreditations

Copyright © Inngot Limited 2019-2025. All rights reserved.

Inngot's online platform identifies all your intangible assets and demonstrates their value to lenders, investors, acquirers, licensees and stakeholders

Accreditations

Copyright © Inngot Limited 2019-2025. All rights reserved.

Inngot's online platform identifies all your intangible assets and demonstrates their value to lenders, investors, acquirers, licensees and stakeholders

Accreditations

Copyright © Inngot Limited 2019-2025. All rights reserved.

Inngot's online platform identifies all your intangible assets and demonstrates their value to lenders, investors, acquirers, licensees and stakeholders

Accreditations

Copyright © Inngot Limited 2019-2025. All rights reserved.